Black Midwife Herstory

Our Timelines Highlight the Roots of Black Midwifery and the Birth Justice Movement

Learn about the historical milestones that shaped the Southern Roots of Black midwifery and discover how the birth justice movement came to be.

Common Ancestry

Black midwifery in America today is a tapestry woven from the stories of Black people from diverse backgrounds. Black midwives have shared legacies and histories, bonded by the richness of African ancestry and the Afro-experience, whether they identify as Black, African, African American, Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Brazilian, Black British, Afro-Latinx, Melanated, or African descended: Africa.

This is where our story begins.

Traditional Knowledge of Childbirth Precolonial Context

Traditional knowledge about attending to birth existed in Africa for thousands of years, like in many cultures across the world. Wherever there have been birthing people, there have been birthing attendants–for millenia. The beliefs, ideas, rituals, tools, approaches, and methods that African people devised for birth are as varied as African identity itself, ranging across region, ethnicity, and historical experience. These traits were passed down from generation to generation, adjusting, evolving, and adapting with time, context, innovation, and change; but there are some key threads that tie traditional African birth practices together: the use of plant medicines, the value of rituals, a strong sense of spirituality, and participation of community in pregnancy, birth, and postpartum care.

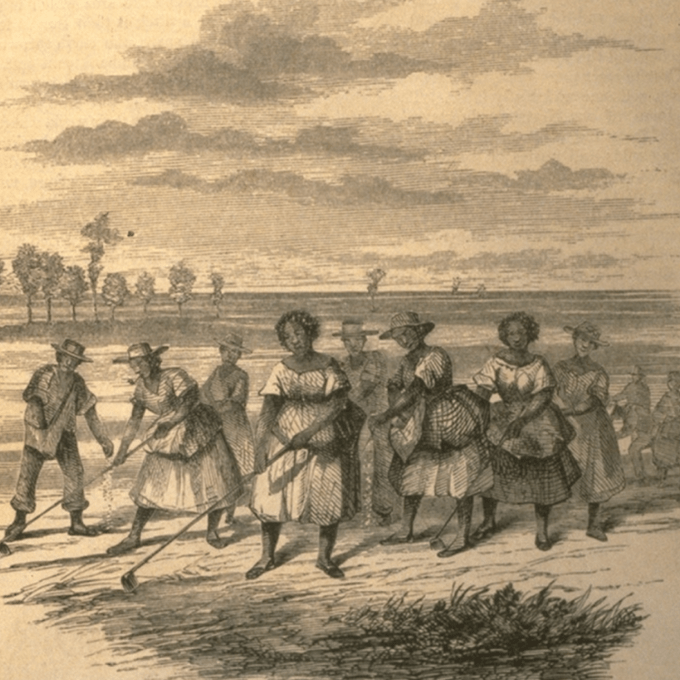

Transatlantic Slave Trade

(Ma’afa: Swahili word for disaster, terrible tragedy)

The first Black midwives in the Americas and on American soil were among the African people that were captured in the slave trade, forced against their will, and transported to colonies in the Americas where they were enslaved. They would have brought with them knowledge and ideas about birth and healing from their own cultures. Most of them came from regions across West and Central Africa, places that include areas in Senegal, Mali, Angola, Ghana, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Africans In America

Our ancestors also brought nuances, customs, and attitudes unique to their culture with them as well as a variety of trades and skills. They were blacksmiths, artists, griots, priests, priestesses, warriors, woodworkers, weavers, herbalists, storytellers, cooks, and midwives.

Passing Down Traditions

Passing down African-based cultural knowledge is one of the primary ways enslaved people participated in resistance and in retaining a sense of their identity in the context of trauma.

Honoring Black Midwives in Enslavement

During chattel slavery in the United States, enslaved midwives, or grannies as they were called, fulfilled an important role, particularly on plantations in the South and attended the births of both Black enslaved people and white families.

MIDWIVES' ROLE ON THE PLANTATION

A DUAL ROLE

Some enslaved midwives also participated in acts of resistance, however, such as providing abortions*1, giving updates that would delay a postpartum person’s return to work in the fields*2, or deliberately using birth healing traditions that were scorned or forbidden by whites around them.

HEALER & RITUALIST

Some practices included “covering the umbilical cord of each newborn with a piece of scorched linen,” wrapping “the mother’s abdomen in a white “belly band,” and disposing of the placenta, “so that it could not be mishandled for ill purposes.”

The midwife was also attentive to unique circumstances, for example, when an infant was born with portions of the amniotic sac on its face. This was called the “veil” and signified a child gifted with spiritual sight. Enslaved midwives also sometimes participated in the naming of the child.

PASSING DOWN HEALING KNOWLEDGE

Enslaved midwives, like other healers, folk practitioners, and “root doctors,” exchanged their knowledge with other members of the plantation community and also taught women who apprenticed with them during birth. Members of the community also sought the help of spiritual healers if they had specific concerns or requests. This sharing of knowledge contributed to the survival of certain beliefs andpractices. For example, in South Carolina, where many Africans from Central Africa were brought, “slave communities […] fostered the Angolan/Kongo belief that the spirit/soul and the body are joint entities.

SALLY: AN ENSLAVED MIDWIFE IN TOBAGO

An excerpt from an 1829 estate appraisal shows number fifty-five: Sally, a 41-year-old creole woman living on the Invera Estate who is described as “healthy” and having an “appraisal value” of £38. One of three women listed with the same name, we know that Sally was likely born in the Americas and probably gained her skill from another Black midwife as an apprentice.

CHILDBIRTH BEFORE OBSTETRICS IN U.S.

THE FIRST AMERICAN MIDWIFERY COURSES IN THE LATE 1700S

NEW ALLURING BIRTHING OPTIONS & A NEW NARRATIVE OF BIRTH

POST-EMANCIPATION

NUMBER OF BLACK MIDWIVES FROM STATE TO STATE 1920S TO 1980S

The same pattern followed in multiple states. In Alabama in 1942, for example, “there were 2,200 registered grannies; by 1980, there were only 70.”

LAURA CARR: GULLAH GEECHEE MIDWIFE

MOTHER GEORGE

“Mother George owned a ranch and practiced frontier medicine in the Grays Lake area. She delivered babies for Black and white families through the gold rush years and later. When Mother George died, her secret was discovered” – She was assigned male at birth and had been living as a woman long enough for this to have come as a shock to her tiny frontier town.

There is not much that we know about her, but according to the Idaho State Journal the back of a photo found in the Clyde Anderson photo collection was marked with a note “Mother George who lived at Grays Lake and is buried there. She was a midwife and a successful doctor. Her father was a Negro and her mother was an Indian.”

GRANDMA MASON

Before Biddy obtained her freedom, she was forced to travel west by the Smiths, slaveholders who were joining the Mormon migration to Utah. She walked about 2,000 miles behind a caravan of 300 wagons and was responsible for making meals, herding cattle, and providing midwifery care.

TWILIGHT SLEEP & HOSPITAL BIRTHS

TWILIGHT SLEEP & HOSPITAL BIRTHS

CAMPAIGN AGAINST LAY MIDWIVES

However, the birthing work of lay midwives came under microscopic scrutiny and physicians began discrediting midwifery care in multiple ways, including lobbying for legislation to either limit the midwives’ practice significantly or to eliminate midwives altogether.

This combined with the negative racial climate and criticism of Black midwives’ healing traditions led to the persecution of lay overall, and Black midwives in particular.

TRAINING FOR BLACK LAY MIDWIVES

While the older community midwives were being slowly and systematically replaced, there were among them who accepted the mandate of the health departments along with younger recruits eager to serve their community in this way. These new recruits represented a breakaway from the apprenticeship culture among Black midwives, and a mark in a new direction.

MARY COLEY

NURSE-MIDWIFERY

NURSE-MIDWIFERY

BLACK NURSE-MIDWIVES

MAUDE E. CALLEN

Her life was captured by W. Eugene Smith’s photo essay, “Nurse Midwife,” in 1951 in LIFE magazine and brought to national attention.

TRADITIONAL CHILDBEARING GROUP, BOSTON, 1979-1991

AYANNA ADE AND CHILDBIRTH PROVIDERS OF AFRICAN DESCENT, HOUSTON, 1970S TO 1980S

INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR TRADITIONAL CHILDBEARING (ICTC), 1991-2016

With the support of Ayanna Ade and other educators, Mama Shafia Monroe, after witnessing a deep void and lack in birthworkers of color in Portland, Oregon where she had moved her family in 1990, founded the International Center for Traditional Childbearing (ICTC) in 1991 to fill the gap. The years of ICTC were a fervor of rich gatherings among birthworkers of color across the country, seeding, watering and nourishing connections, and collective visions. Birthworkers that attended ICTC recall the incredible sense of community and support they felt in their work. With Mama Shafia’s leadership, ICTC’s mission was to increase the number of midwives, doulas, and healers in order to reduce infant and maternal mortality, increase breastfeeding rates, and empower families. “Its vision was that there be a midwife for every community, a healthy baby born to every family and the midwife as the norm for women of color.”* In 2016, Mama Shafia retired and in the following years, ICTC transitioned into the National Association to Advance Black Birth.

JENNIE JOSEPH AND COMMONSENSE CHILDBIRTH, INC. AND SCHOOL OF MIDWIFERY

Jennie is owner of the first Black privately-owned MEAC-accredited midwifery school.

BLACK MIDWIVES ORGANIZING WITHIN MIDWIFERY ORGANIZATIONS

Since their founding, major midwifery organizations in the United States have done significant work in advocating for the midwifery model of care that centers clients and families and the natural physiologic process of birth as well as honoring the ancient craft of midwifery. They’ve created a variety of key professional resources for practicing midwives across the country. But like many institutions across the United States, organizations like Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA), American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM), and the National Association of Certified Professional Midwives (NACPM) have grappled with racist histories and created hostile environments for midwives of color in the past. Throughout the decades, Black midwives and their allies within these organizations have been persistent, courageous, and clear in their goals to make these spaces truly inclusive for midwives of color.